Year 5, Piece Nine: 25. Green Green

Potions for Spring. Jewish Mysticism. Counting the Omer. Chesed.

For at least as long as the pandemic has been going on, D has made “potions.” It probably started earlier than that, but I remember it mostly in the context of our many (many) hours together on walks (what else is there to do?). These potions mostly or entirely consist of foraged plant matter, leaves and flowers ripped up and put in some sort of vessel. It’s been a learning process for both of us, negotiating about which plants she can touch and which she should leave alone, learning to pick flowers only when there will be many still left.

We were outside together this week just the two of us, somewhat of a rarity. Of course she wanted to make potions. Somehow she located a cinderblock and declared it the perfect container: “You can have that side, and I’ll have this side!!”

D filled hers with what she considered a wide array of flowers and leaves. This week being Green Green, I filled mine only with green things. She declared this boring, and not very magical. She didn’t really buy it when I told her that colors are my magic.

“My potion is for healing people and creatures, what’s yours for?” she asked me.

“Hmm...I suppose mine is for healing hearts,” I said.

“That’s it?”

I mean, healing hearts is a tall order, right? Isn’t that the start of healing people and creatures? I didn’t feel like going down that rabbit hole with her, so we just sat making potions. Eventually though, I couldn't help it. I pulled out my phone to take pictures.

“Mom, you aren’t doing as much as I expected you to do. Just taking pictures,” she complained.

Sure. But isn’t making animations part of my magic too? Isn’t taking pictures a form of devotion? Of signaling to the universe what you want, what you love, what is yours, what is you?

Apparently I generated 26,606 images on my phone in 2020 alone. That’s an average of 70 a day. Many of them are duplicates to create stills for animations, or drafts of animations, or multiple file types. My phone is my studio, after all. But 26,606 is still a lot. And a lot of those are photographs of my children.

Now, I’m not taking the photos for social media. I try not to share the kids’ faces there or much of anything else besides my own art. I take many of the photos to share directly with loved ones and family far away. But a lot I take almost reflexively, as a means to mark and try to hold a moment.

Now that I have a second child, I feel acutely how much the little moments slip through the cracks. How much we already don’t remember about D’s babyhood. “We won’t remember this,” is something Justin and I say often to each other incredulously when something small and wonderful happens: a funny pronunciation of a word, or being led to look at something by an impossibly small hand. Maybe it’s a way of simultaneously celebrating it and releasing attachment. The gesture of taking photos might be an opposite gesture, one of grasping, of capturing. Pulling out the phone to take a picture is still a celebration though: it says “This. I love this. I appreciate this.”

But pulling out the phone also disrupts the very moment it is trying to capture. Does photographing it mean I get to hold on to it somehow? To keep it? Or do the photographs replace the memories, become the only memories?

I can claim that taking pictures is part of my magic, but it doesn’t seem to pass muster with this four-year-old. She sees it for what it is: a separation from being with her in the present moment.

Perhaps I have so over-intellectualized my spirituality that I can’t be fully in this moment without trying to link it to a future moment. Or a past one.

But isn’t that partly what religion is about? Especially calendar-oriented religions like Judaism? Linking moments together throughout the day, the month, the year, the years, through the ages. Assigning great significance to otherwise arbitrary things and making them holy over time through repetition.

Just about any symbol set could be used as a tool to notice and sanctify connections in your life and environment. I mostly embrace my Jewish heritage and its rituals and symbols. Lately, I have also chosen color. These are not mutually exclusive, and in fact may inform each other. You could also really use almost anything: numbers, letters, cards, stars, tea leaves, bones, conversations. I wonder then whether the meaning I derive from color arises from my own associations over time or objective classifications arising from the nature of the colors themselves. Probably both.

But what happens when you switch systems of meaning entirely, using the same symbols but with different meanings?

This week is Passover, or Pesach, the Jewish holiday celebrating the passage from bondage into freedom and the perpetual struggle for collective liberation. Passover is also the Festival of Spring: at the ritual Seder meal we symbolize this by placing a green leafy vegetable on the Seder plate, often parsley. This green vegetable is called “karpas” and it has its own blessing.

So drawing Green Green this week immediately evoked Passover for me. I even made sure to include parsley in that backyard potion. But this week, and the next seven weeks, the colors are going even deeper than that.

Disclaimer:The following is about to get pretty esoteric, or at least very specific about religious and spiritual practices.

There is a 50-day period between Passover and the next Jewish holiday of Shavuot. If Passover is about becoming free, Shavuot is about receiving the Torah, or the means to living a righteous life. These are also each agricultural holidays: two out of the three harvest festivals during the year, when Jews would take their first harvest to the Temple, the other one happening in the Fall with Sukkot.

On the second day of Passover, an offering of an “omer” of the first barley harvest was taken to the temple, where the priest would use it in a “wave offering,” waving it in the six directions: north, south, east, west, up, and down. Only then could that year’s barley harvest be eaten.

From that day on, it is commanded to count 49 days until the 50th day of Shavuot, when Jews would bring the wheat harvest to the temple. This is called Counting the Omer. This entails, well, counting. Literally. Every night (on the Hebrew calendars, days start at sundown instead of at midnight) you say a series of blessings and you count, like so:

“Today is Day One of the Omer.”

“Today is Two Days of the Omer.”

On and on until:

“Today is Forty-Eight Days, which are Six Weeks and Six Days of the Omer.”

“Today is Forty-Nine Days, which are Seven Weeks of the Omer.”

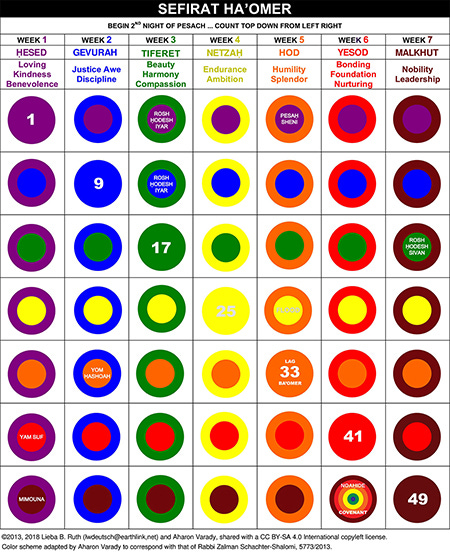

It doesn’t stop with numbers or the harvest. If Passover celebrates going from slavery to freedom, there was still so much healing for the Israelites to do before they were ready to recieve the Torah on Shavout. So these 49 days become a sort of spiritual healing program, following a 7 x7 grid of holy attributes, or sephirot in the Tree of Life of Kabbalah (Jewish mysticism). Each week has an overarching attribute, and each day pairs it with one of the other attributes, cycling in a 7 x7 grid, like so:

Yes, this is basically like a 49-day sprint of Rainbow Squared. Or perhaps more accurately, Rainbow Squared is like a 49-week marathon of Counting the Omer.

I’m still processing the similarities here, which are staggering. I knew about the Omer, but I didn’t really know about the attribute matrix, and I certainly had never seen it represented in colors. In that way, it did not consciously influence the Rainbow Squared grid, which I really conceived as a formula for artistic discipline. It is perhaps no accident though that these last five years has brought my practice closer to this Jewish practice.

So this year, for the first time, I am counting the Omer. It is a commitment, but I like those. And I am not doing it alone: while each night blessings are done on my own, I am engaging biweekly with a creative cohort called “A New Gift” who is doing the same.

While I am in this 49-day process within my otherwise 49-week cycle, I’m going to think about each week’s overarching attribute and how they relate to colors. These attributes are hard to translate, and every source seems to have a different take. They each also have multiple meanings. The attributes or sephirot go as follows:

Week 1: Chesed - Lovingkindness, Unconditional Love, Grace, Mercy

Week 2: Gevurah - Strength, Judgment, Boundaries

Week 3: Tiferet - Harmony, Balance, Beauty

Week 4: Netzach - Eternity, Endurance, Dedication, Ambition

Week 5: Hod - Splendor, Awe, Humility, Acceptance, Order

Week 6: Yesod - Foundation, Creativity, Bonding, Sexuality

Week 7: Malchut (Shekhinah) - Divine Presence, Physical Reality, Manifestation, Leadership

So how do colors fit into this?

There are just as many color associations as there are meanings of each of these individual sephirot. In some systems, the colors are determined one by one, and in others they follow a certain rainbow order. The grid above uses the colors determined by Rabbi Zalman Shachter-Shalomi, or Reb Zalman, the founder of the Jewish Renewal movement, as laid out in his rainbow tallit design.

In Rainbow Squared, Green Green is the very center of the grid: the middle of the journey, or perhaps the core from which all things emanate. Its significance is love, family, plants, Earth, opening your heart and living from it.

I think that Green might be a pretty good match for Chesed, the attribute for this first week of the Omer count. Green Green is where I have always located unconditional love and connection to the Earth. Chesed is also unconditional love, its full week always showing up right at the start of the festival of spring. The cycle of plant growth is connected to our ability to love unconditionally, its own kind of bursting into bloom, into what Taya Mâ Shere and Nomy Lamm call “heart expansion.”

It’s also no accident that love, grace, and mercy would be where we start the journey away from slavery into freedom. Slavery is an old story, but it isn’t over. Here is the United States we are still living daily in the deep effects of slavery, with a long, long road of repair ahead (one step on that journey may be passing H.R. 40). And there are so many people still enslaved today around the world. Some in ways that are abhorrent and easy to renounce though hard to see like sex trafficking. Some in ways we don’t often acknowledge or accept like the oppression of the many unseen people behind the creation and distribution of the goods we all think we depend on, who have no choice but to submit their lives to this cause.

Chesed means seeing beyond the self, opening your heart until you can no longer tune out the oppression of others, especially when you might personally benefit from it.

Color it green, color it purple. Call it love, call it lovingkindness. Let us this year call it collective liberation, every year and every day until it’s true.

Maybe that’s what my Pesach potion is for.