I only had about twenty minutes to pull the next card while the kids were out of the house. So I sat down and got to work, doing a quick meditation, laying out a scarf to spread out each of the previous cards, and shuffling the deck. All the while though, I could hear a dog crying outside of the window.

It was the dog we share a yard with, a black miniature poodle named Fannie. I often feed Fannie when her owner is working long shifts at the hospital as a midwife, so we are pretty familiar with each other. I knew that her owner was working that day, and that Fannie was probably whining because she was lonely. Still, I barely had enough time to do what I needed to do, so I tried to ignore it.

As I continued shuffling, I tried to think about something else, or tried to think about nothing, I suppose. But as the four remaining cards passed through my hands, one in particular popped into my mind: Red Blue, Body and Communication. Communication within the body and between bodies. Nonverbal communication.

Fannie’s crying was an example of Red Blue right in front of me. Okay, okay, this was some nonverbal communication I needed to pay attention to.

I put down the cards and went outside to play with Fannie for a few minutes. I pet her and reassured her, amusedly noticing my red sweatshirt against her blue hand knit doggie sweater. “Wouldn’t it be magic if…?” I had the thought, but tried not to get too attached. Fannie calmed down, and I went back inside to draw the next card.

I guess I don’t need to tell you that the next card was Red Blue. The probability was 1 in 4. Not terribly low, but low enough to feel special.

Animals learn to cry to get attention. I suppose they don’t even learn, many are born doing it. In mammals, this crying is sometimes referred to as an acoustical umbilical cord. Before birth, the fetus communicates on a biological level through the umbilical cord and the placenta, having all of their needs met directly. Once the cord is cut and the placenta is buried or consumed or otherwise discarded, baby animals get their needs met by crying.

What makes humans unique among mammals is that we keep crying even after babyhood, even after we no longer need our parents’ attention (for survival anyway). Maybe that’s why domesticated pets cry too, a trait compatible with their human caretakers.

How appropriate that while my neighbor was delivering babies her dog was crying for attention.

Red and Blue often make me think of babies anyway. Tiny humans are the ultimate nonverbal communicators precisely because we expect them one day to express themselves through symbols instead of screams.

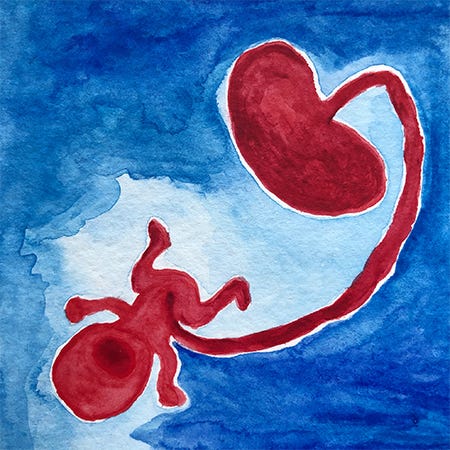

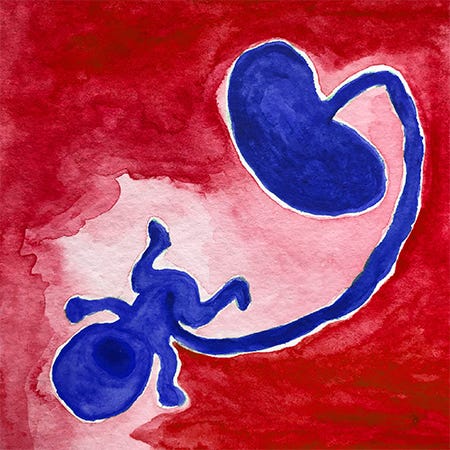

The very first piece for Blue Red was the painting above, a screaming baby still attached to a placenta.

When Red Blue came up this week it had me thinking about placentas again, but this time for a different reason.

I was thinking about placentas because I was thinking about viral DNA, and I was thinking about viral DNA because I got a COVID booster shot. Vaccines are themselves a certain type of nonverbal communication. Perhaps mRNA vaccines even more so than traditional vaccines: “m” stands for “messenger.” I tried to imagine my immune system making sense of the new genetic material that had just burst forth into my left arm. It was strangely humbling, realizing how little I understood the actual physiology. But it was also strangely intimate.

Beyond the act of injection, the presence of genetic material from other organisms or even other organisms themselves inside your own body is nothing exceptional. In fact, it’s the norm. Microbial cells outnumber human cells in our bodies, from some figures by 10 to 1 but more definitively by at least 1.3 to 1. The microorganisms that live on our skin, in our mouths, in our guts, in our vaginas, and our feces play perhaps as integral a role as many of our own human cells. Our microbes are part of who we are. And even within our microbiomes, viruses are by far the most plentiful organism, also by 10 to 1.

But what is perhaps wilder than the sheer number of viruses cohabitating inside each of us, is how much viral DNA is present in our own human DNA: 8%. 8%! 8% of our DNA is thought to come from ancient viruses. Known as endogenous retroviruses, these viruses entered the DNA of mammal ancestors, impacting so-called germ cells like egg and sperm to be passed on to subsequent generations. Some of this DNA might be helpful, some might be harmful, some benign. And some define what it means to be a mammal.

One of the most important biological tricks we picked up from this ancient mass cross-species communication? The placenta.

As the podcast Radiolab recently explained in an episode titled “Everybody’s Got One”:

A virus infected an ancient proto-mammal and changed its DNA so that, eventually, many generations later, the eggshell transformed from a hard shell that exists outside the body to a sort of permeable layer that exists inside the body, which then becomes the placenta. And this was a huge advantage because it made it possible for the blood of the mother to actually feed the fetus. So it could get tons more nutrients. It wasn't limited to just, like, whatever yolk was inside the egg from the beginning.

I had already thought placentas were fascinating organs. I had never even considered how they might have evolved. (If you don’t know much about the placenta, or if you love placentas and always want to learn more, take a listen to that episode. Or cheat and read the transcript like I often do.)

Most other creatures don’t act as hosts to their fetuses or feed them from their own (red and blue) blood stream. Which is to say nothing of another mammalian trait, continuing to feed babies from our own bodies after they are born. Growing inside of another body is one of the wildest universal features of human existence. The fact that this was made possible by a temporary organ whose code was inserted into our biological ancestors’ DNA by a microscopic organism that may or may not be alive is nothing short of mind blowing.

Learning that the blueprint for placentas came from ancient viruses was a pretty big paradigm shift for me. Enough that it seemed fitting to invert a Blue Red image into Red Blue:

I mean, what the hell does it mean to be human anyway? To be alive?

This where pictures can perhaps do better than words. Can maybe evoke the feeling of smallness and splendor that comes from knowing that your big animal body is a composite of the stories of so many other types of bodies. That you carry these stories in every cell, that they’ve been carried for so long before you and will be so far beyond you. Taken at the macro and micro level, all beings coexist in one giant, ongoing, immensely complex communication. Communication constitutes our very coexistence.

Viral mutations made us the mammals we are. Millions of years later, the COVID-19 virus has turned human bodies into a mass communication technology, an automated and globally distributed viral factory. Humans have in turn developed our own communication technologies to turn off or slow down this production.

Vaccines teach our bodies to recognize COVID-19: another opportunity to learn from viruses. But the real learning here is not within our bodies but between them.

This virus is teaching us that the personal and the systemic are linked. Your choices are collective, and taking care of yourself is a way of taking care of others. Yet this virus also teaches us that taking care of yourself won’t work if others aren’t taken care of too. Without universal access to vaccines and health care, personal access can only be so effective. Taking care of each other is the only way to take care of ourselves.

And again a virus teaches us how to be human.